Tuesday, December 1, 2020

New Online Book Club: Journeys in Words - From Galway to Dublin - starting Tuesday, 8 December

Following on from the highly successful Eilís Dillon Online Book Club, I'm delighted to let you know that I'm working with Galway Public Libraries on another exciting odyssey through words which focuses on two great Irish writers of the 20th c: Maeve Brennan and Liam O'Flaherty.

During the 'Journeys in Words' book club we'll be traversing from East to West coast, from 1920s suburban Dublin to the rugged, elemental settings of Inis Mór. Fasten your seatbelt, grab your book, sit back and relax to join us for this journey! We will start by looking at Maeve Brennan's stories in The Springs of Affection (Stinging Fly Press, 2016) this month and continue with O'Flaherty's Irish Portraits: 14 Stories (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012) after Christmas. Running for one hour, from 7pm - 8pm each session, our dates are: Tuesday, 8 Deecember Tuesday, 15 December, Tuesday, 5 January and Tuesday, 12 January 2021. See the full schedule below.

Membership is always free but places are limited and tickets are available on a first-come-first-served basis. Click here to book your place! #galwaypubliclibraries #maevebrennan #liamoflaherty #greatirishwriters

Thursday, November 26, 2020

Eilís Dillon Centenary Free Events Online - Politics & Patriotism seminar this evening

Despite all the challenges of 2020, Galway's own internationally acclaimed writer, Eilís Dillon (1920-1994) has been enjoying renewed appreciation and celebration in her centenary year. It has been a privilege to be part of some of the many events on her life and work that have taken place - some just before lockdown in early March - and others [fully socially distanced] since October and November. Galway Public Libraries have been busy commemorating Dillon and reappraising her legacy in a weekly book club during October (which I was honoured to facilitate), in education with the 5 Islands One Author project with Sadbh Devlin and also in three seminars exploring Dillon's times and writings around her politics and patriotism, historical fictions and detective novels (with special art and music commissions also ahead). The first of these seminars, Eilís Dillon: Politics & Patriotism, will be streamed online this evening at 7pm and features poet and Dillon's daughter, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Dr. Cathríona Clear and Honor O Brolchain, Dillon's niece and yours truly as convenor. Special musicians featured are Carmel Dempsey and Tomás Mannion. Visit the Galway Public Libraries YouTube channel and tune in to this unique event which integrates discussion with readings and music.

Tuesday, November 3, 2020

Some recent projects and publications

“Music is colours and time in rhythm,” remarked Claude Debussy, memorably. One wonders if he was actually synaesthetic, ie. if he experienced sound as colour, or perhaps what he is referring to here are the tonal textures of music. Whatever his intention, Debussy is a fascinating composer, often credited with pioneering musical Impressionism, (though he had also some issues with that particular term) so I was thrilled to be invited by Maeve Bryan of Galway Music Residency to participate in their Creative Responses project. The task: to respond in poetry to Debussy’s String Quartet in G Minor, as performed by ConTempo - Galway’s wonderful quartet-in-residence. Composed when Debussy was just 31, this work in G Minor is his only string quartet, and what a dazzling opus it is. I'm always up for an ekphrastic challenge as well as the adventure of collaboration, (and have long admired and appreciated ConTempo's brilliant work) so this was an immensely enjoyable project to sink my teeth into. The only tricky part was grabbing a figurative bite to chew on since this piece dances, vacillates, heaves and swoons all over the place! Bursting with ingenuity, Debussy’s opening theme moves with a vibrant staccato swagger through various shades of interrogation, doubt, anger, whimsy, nostalgia and a final decisive resolution, that is utterly altered, but unequivocally firm. I tried, initally, to write a line-by-line rhetort to the changing moods of the piece, but eventually plumped for a different approach: to use one of the more curious lines that came up as a springboard for a poem that would also have a kind of syncopated sonority, oscillating in tone and movement. I corralled the following sentence to explore and unpack further and had plenty of fun along the way: “What would it look like if I were to modulate out of Mum into another mode?” The premise: a busy mother with a full morning of freedom ahead of her leaves the chores to one side and let her thoughts meander and feelings fulminate... So I ran with this and am pleased with the resulting poem, which is read beautifully by Maeve Bryan in the video clip below, with Debussy's composition following immediately after, along with many stunning visual responses to the music by a host of exciting artists from Galway and Mayo. I hope you enjoy it too!

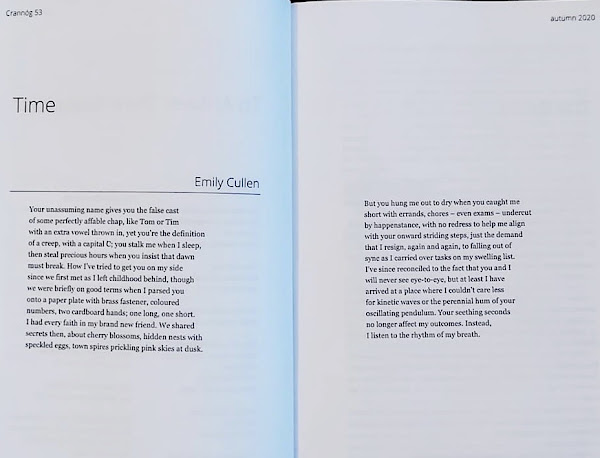

I’m delighted, also, to have a poem entitled “Time” in the current Autumn 2020 issue of Crannóg magazine. This Galway-based international publication has a special place in my heart and it’s great to learn that this edition - no. 53 - has already gone to a second printing. Their biggest issue yet, it features 45 poets and 9 fiction writers.

Because of the lockdown, there was no launch event for issue 53, but if you’d like to purchase a copy you can do so here.

Below is my poem, “Time” which features in Crannog 53 and captures something of my ongoing turbulent relationship with the eponymous entity! I hope you like it.

Tuesday, October 27, 2020

Online Poetry Courses starting soon ... book your place now

"Perception is the first act of the imagination," wrote William Carlos Williams. Would you like to devote more time to perception, imagination and your poetry practice over the coming Winter weeks? Want to immerse yourself in vivid poetry that works on a number of levels while composing new poems of your own and learning approaches and techniques to expand your knowledge and sharpen your craft? I am delighted to announce that I will be running online poetry courses starting in early November and running for six weeks. The courses are ideally aimed at emerging poets or those who have some experience writing poetry and may have started to publish their poems, but advanced writers will also find stimulation and encouragement. As someone who has greatly enjoyed teaching courses on Creative Writing (to undergraduate students at the University of Melbourne and at NUI Galway) and Appreciation of Poetry (to adult learners at NUI Galway) for many years, I agree with poet, Theodore Roethke's observation that "teaching is an act of love, a spiritual cohabitation, one of the few sacred relationships left in a crass secular world." For these online courses, I am keeping group sizes small to create and maintain a warm, supportive atmosphere and a safe space for creativity to flourish. I’m also keeping costs low because of these challenging pandemic times we are all living through. We will begin at 7pm on Thursday, 5 November with duration about an hour or just over. There are a couple of spaces still available. To find out more and book your place, please contact me now on: emilycullendavison@gmail.com.

Wednesday, October 7, 2020

Eilís Dillon Book Club starts tomorrow...

The past week has flown and I'm delighted to announce that the Eilís Dillon Book Club is now full with 25 members having signed up. Our first session takes place online tomorrow (Thursday, 8 October) at 7pm. Taking her novel, The Bitter Glass (1958) as our main focus, the Eilís Dillon Book Club will also discuss the author's life and legacy and feature special guests each week, including her daughter, renowned poet, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, son, Cormac Ó Cuilleanáin, Anne Marie Herron, Siobhán Morrissey and Maureen O'Connor. In our first session we will ease into the book by chatting about our initial impressions of the text with a special focus on the Galway scenes and the world Dillon is creating.

The Bitter Glass is an ideal choice for Galway’s Great Read, I think, for a number of reasons: 1) the book is set in Galway city and county and includes many lush descriptions of the landscape, the sea, the Connemara people, folklore and rich nathanna cainte or turns of phrase; 2) its plotline is engaging throughout, yet artfully simple – it keeps us compelled to read while the story arc is cohesive and enjoyable; 3) the time period in which the book is set – 1922 during the Irish Civil War – is resonant and, as such, addresses themes from our history that are especially notable in this second phase of the Decade of Centenaries; 4) the story is well told in prose that is clear and lucent and 5) last but not least, it is written by a homegrown talent – a true Galwegian. If you'd like to join us in spirit, we'd be delighted. The Bitter Glass is now available to read via Kindle here. (If you don't own a Kindle, you could download the Kindle app to your device). You can also read a sampler of the first three chapters of the novel for free on the Eilís Dillon website.

Below is an outline of what we'll be exploring at the Book Club over the next four weeks. Happy reading!:

The Eilís Dillon Book Club is presented by Galway Public Libraries as part of Galway's Great Read funded by Creative Ireland, Galway County Council and the Decade of Centenaries.

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

Announcing the Eilís Dillon Book Club as part of Galway's Great Read

The name Eilís Dillon always had an intriguing ring for me. I recall the book cover we had at home with its curious title, Across the Bitter Sea, and the world-weary, sphinx-like gaze of its dark-haired heroine on the cover, gently confronting the reader, with a crumbling ruin of a Famine cottage in the background, an ocean and a seated gentleman.

I knew the book had that sweeping ‘saga’ look about it, but to my child's eyes, it seemed like something of a tome - too large and prohibitive to navigate. So, it was not until relatively recently that I finally got my hands on a copy of the novel that had graced our shelves in my childhood home in Carrick-on-Shannon, and knuckled down to reading it. Ambitious in its historical time span (1851-1916) and thematic reach (post-Famine up to the Easter Rising), yet written with a fluid and compelling touch, it's no wonder the novel achieved bestseller status when first published in 1973.

After years of being unfairly neglected, Eilís Dillon is a name to conjure with once again. So many Irish households own at least one copy of an Eilís Dillon novel and yet we hear so little about her. Why so? Now, in her centenary year, it is heartening that there are celebrations taking place throughout October and November across Galway city and county and I’m delighted to announce that, as part of Galway’s Great Read, I will be facilitating the free online Eilís Dillon Book Club for Galway Public Libraries throughout the month of October.

“I was born, in Galway in 1920, into a world of ghosts”, Dillon wrote in her captivating memoir, Inside Ireland (1982) and we will be unpacking what exactly the writer meant over the course of the book club sessions with a special focus on her 1958 novel, The Bitter Glass - the first of the six historical novels written by her.

I decided to explore The Bitter Glass because of its richness as a socio-historical document of the civil war era in Ireland (relevant in this decade of centenaries) and as a novel that evokes the whitewashed homesteads and turf-fires of Connemara. Eilis Dillon’s West-of-Ireland sensibility and deep feeling for the landscape and its people pervades her books, offering glimpses of the songs, traditions and folklore of the Galway hinterland. While Across the Bitter Sea is probably her most famous novel, The Bitter Glass is a quiet work of art with its simple storyline and tense plot that raises subtle, yet haunting, questions around the 'Irish conscience' and that also explores themes of confinement, especially apt in our pandemic era. Gripping enough to read in a couple of sittings, I know it will be ideal for our book group discussions. I was also impressed to discover that the book was included in the Peter Boxall's 1001 Books you must read before you die compendium and that the great Eudora Welty was "completely won by it...the world of Connemara was flawlessly conveyed". Each week, on Thursday evenings from 7pm, (beginning on 8th October), we will focus on particular passages in the book, discuss the novel’s themes and also have a chat with a special guest who will enrich our understandings. With the truism of its very opening sentence, proclaiming that: “Galway was like a different world”, how apt that it is Galway's Great Read for 2020!

To register for a place click on this link and be sure to sign up for each of the 4 sessions. I look forward to chatting with you about this fascinating and highly versatile writer. The first three chapters of The Bitter Glass are now available to read for free on the Eilís Dillon website here. The book will also be available via Kindle very soon. Happy reading and I hope you might join us for what promises to be a fun and engaging exploration of a truly gifted writer!

Thursday, September 3, 2020

Book review: One Hundred Views of NW3 by Pat Jourdan

Renowned author and artist, Pat Jourdan's new novel, One Hundred Views of NW3 paints a vivid picture of London in the early 1960s through the eyes of Stella, recently graduated from art college and finding her feet in the world. With her clear aesthetic vision of the 36 scenes she is going to paint, Stella accrues much more material from life than she bargains for.

A kind of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman, without the egotism of Joyce, Pat’s painterly eye observes small, mundane realities through a fresh lens; her detached, autofictional voice looks askance at her own 20s as if through an artist’s viewfinder. We witness her internal thought processes making sense of each scene as it unfolds around her – a curious combination of the bohemian and the pragmatic. With Jourdan’s characteristic flair for detail, the book is shot through with nuggets of psychological wisdom, insight (there many fascinating asides gleaned from Stella’s Liverpool art school training) and a searing honesty about her struggles. Her lost tampon vignette is like a whole new feminist antidote to John Donne:

“Making contact with the magic little thread was like discovering radium or America; suddenly there was hope. The next worry was that by tugging at this little strand she might break it. It had never done, ever, before but there could always be a first time. In fact Stella had never thought of it. Writhing about, rolling over on this dirty carpet, she felt in sight of success. A lookout in the crow’s nest. Land ahoy.” (p. 38)

We witness Stella’s hard-won lessons about the grasping, predatorial men who leave her to pick up the pieces as they drift in and out of her life. Though never didactic or preachy, this book will certainly consolidate your feminist sensibilities. (How were standards for men ever so low and so acceptable?!) The topography of London is laid out seamlessly as Clapham Common, Shepherd’s Park, Stockwell Green/Road, Hampstead Heath and many other locales are brought to life, while the excitement around the burgeoning poetry scene is palpable. One Hundred Views of NW3 is also a social document of a time when smog filled the London air, the Vietnam war was waging and Tom Jones’s “It’s Not Unusual” topped the charts. Often struggling to pay her rent and to afford her next meal, the book highlights the plight and privations of young artists who have to find ways “to get by in other occupations”. I also read it as an indictment of a system and a time that was hostile to fledgling female artists starting out with no supports in place, and when work as a secretary, nurse or cleaner was an unavoidable destiny. Opting for the latter, Stella joins the ‘Daily Maids’ agency and notes that:

“it was impossible to draw or sketch at work even when a house or flat was empty. But she always kept a small notebook in a pocket for any rapid lines of poetry that might occur, worried that if not written immediately, they would disappear forever. Otherwise entire days were wasted with nothing to show for her efforts. The houses re-dirtied themselves, there was no result much longer than an hour. So much of the work ordinary people did was like this; untraceable and repetitive.” (p. 62).

Pat’s poetic gifts for language also pervade the book. On her first date with Dave, she is led “through galleries towards the showcases filled with clocks. The ticking of so many timepieces together made a clacking sound as if these hulking grandfather and grandmother clocks were chattering together over centuries while London traffic milled about outside in messy chaos.” (p. 7). Pat gallantly changes the names of her characters so we are left wondering about the identity of many of the seriously dodgy male poets in the book, especially ‘Stu’. The renowned female poet, Stevie Smith, is the only one permitted her true name. What is apparent, however, is that we are smack bang in the era of the Mersey Sound poets when even Ginsberg himself trekked to the UK to check out the new craze for poetry. Glancing at my second-hand copy of The Mersey Sound Penguin Modern Poets now, I’m struck by the gaping lack of a female poet in the slim volume - containing Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Brian Patten - though, tellingly, a maniacal female ‘fan’ is depicted on the cover, reminding us that women were clearly perceived as the accessories and the cheerleaders, rarely ever the art-makers. (Interestingly, much of the poetry in The Mersey Sound doesn’t hold up so well at a remove from its time, looking rather trite and self-involved now).

One Hundred Views of NW3, on the other hand, is perfectly paced with just the right mix of wisdom-laced narrative summary and lively direct speech to keep us wanting more. What shines through, indomitably, is Stella’s genuine interest in people and curiosity about the world around her, no matter how tough her travails. She is never self-pitying through hardships and heartbreaks, but always a remarkable combination of pragmatic and inventive. And, most of all, she finds true elation and 'natural highs' in her art and in the creative process: “It was being an artist after all that was important.” This book’s combination of heart, great prose and insight into early ‘60s England makes it a compelling and rewarding read. One Hundred Views of NW3 is available now from Amazon in both print edition and Kindle editions. See: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Pat-Jourdan/e/B001K7ZMWI%3Fref=dbs_a_mng_rwt_scns_share

Sunday, May 3, 2020

More poetry updates: Roscommon Schools' Poetry Prize & my first YouTube reading

Before the global COVID-19 pandemic, I had just started as poet-in-residence at Scoil Phobail Mhic Dara in Carna, in the beautiful Connemara Gaeltacht. At NUI Galway, I was able to move my last Creative Writing seminars of the semester online. I was also looking forward to giving a reading at the wonderful Strokestown International Poetry Festival this weekend with poet, Simon Lewis. While event cancellations and postponements are unfortunate for everyone involved, the most important thing is that we are all staying safe, remembering that "our health is our wealth".

On a positive note, it has been uplifting to judge the Roscommon Schools' Poetry competition for the Strokestown Poetry Festival and to read so many poems of every day celebration from primary and secondary students. The winners of the competition - for both primary and secondary schools - were officially announced on the Festival website today. I read over 450 entries "blind" in batches, so I was delighted to see a good mix of boys and girls among the winners and highly commended poets (see the list of winners and highly commended poets below)

Visit this link to read the winning poem from both primary ("Earth"), and secondary ("Lunatic"), schools. My individual comments have been sent to the recipients and I look forward to watching out for the names of these fledgling writers as they make their first incursions into print. I'm grateful to Strokestown Poetry Festival committee for asking me to judge the competition.

In other exciting news, I gave my first live reading on Youtube for The Holding Cell last Wednesday, 29th April at 7pm and you can watch the reading below. It was an exhilarating experience; slightly nerve-wracking but also highly enjoyable. Huge thanks to everyone who tuned in and eased me on my maiden voyage with technology - it certainly helped! Though it feels a little odd for me to invite 'subscribers', I plan to announce future short readings in the not-too-distant future, now that my new YouTube channel is "off the ground". The best way you can find out about upcoming releases is to click the 'subscribe' tab on the page and so I encourage you to do so.

Hats off to the wonderful Simon and Rozz Lewis for taking the brilliant initiative of setting up the Holding Cell during this time of global crisis and thanks so much to them for inviting me to read. Like some of the other poets involved, I would have been reluctant to take the plunge without their encouraging nudge. For a full line-up of readers and schedule of readings, check out The Holding Cell website here.

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

A tribute to Eavan Boland

My head is full with Eavan Boland this evening. She has left us too soon, (she passed away suddenly yesterday at the age of 75), and the country is in mourning for its great national poet. After years of enjoying her poetry, I felt blessed to finally meet her in the Summer of 2018, when I was one of eight poets selected to participate in a masterclass she was leading for Poetry Ireland during the Kilkenny Arts Festival. When Eavan entered the room, there was a palpable hush of admiration. During the next two hours, Eavan rigorously assessed and dissected a poem by each of us. To observe a master at work is always a privilege and a delight. We were all deeply impressed by her incisiveness and verbal acuity as a brilliant “line editor” – the term she humbly applied to herself that day. She only had to appraise our drafts quickly to grasp the core of the piece and what it had the potential to become.

Magnanimously, she also invited us to send her one additional poem by email after the workshop, to which she would respond soon with suggestions. On 27 August 2018 I was fortunate to receive a considered reply in which she wrote with gentle encouragement about one of my stanzas: “I know that making a cut can be painful. But there might be some argument for making it here.” She also found the Achilles heel of my draft – a didactic tendency in the exposition – and wrote the following: “In summary there really is so much of worth and energy in this poem that I think it would really benefit from revision. Didacticism is a temptation for every single poet, and is worth resisting! But without it there is an eloquent strong poem here.” How sage and true her advice. I remain on guard now for a whiff of didacticism in my writings, knowing that I will treasure the message she sent me. Poetry is a lifelong journey and apprenticeship, and I keep the photo taken of us all with Eavan that day above my desk to nudge me not to stint or slacken in my creative efforts.

|

| Eavan Boland (1944-2020) RIP |

|

| Eavan Boland (centre) with the participants of her masterclass, August 2018. L-R: Paul McCarrick, Noelle Lynskey, Liam O'Neill, myself, Eavan, Fiona Smith, Alice Kinsella, Fiona Bolger & Breda Joyce |

I don’t claim to be an expert on Eavan’s corpus of work by any means. However, I have had some occasions for close reading her poems when I explored them with undergraduates in Irish Studies seminars at NUI Galway (her poems about Irish migrant experience and the liminal spaces of the diaspora) and her poems about the Famine and the Irish landscape (such as "Quarantine", "That the Cartography of Science is Limited" and "The Famine Road") with American exchange students from Villanova University who were at NUI Galway for the semester. The latter poems, in particular, impressed my exchange students who were rendered speechless, with glassy eyes, when they googled ‘famine roads’ only to discover maps with meandering boreens like tributaries that tapered off into nothing, before ever reaching the ocean. They were dumbstruck at the calculated cruelty of Lord Trevelyan and his committee. Eavan bravely squared up to the great tragedy of the Famine through the lens of art, expressing the ineffable when few others were attempting to do so. In tackling the patriarchal hegemony of the Irish canon, her immersion in, and engagement with, Irish culture and the Irish tradition was profound. Lulled by the romance of the 18th century Aisling tradition and by the sovereignty myths of Banba, Eire and Fodhla, I confess that I hadn’t critically considered the import of the figuration of Ireland-as-woman for myself as a young Irish female writer until I read Eavan’s book, Object Lessons. "I could not a woman accept the nation formulated for me by Irish poetry and its traditions," she wrote, rejecting a "fusion of the national and the feminine which seemed to simplify both."

In terms of my own developing body of work, as a new mother living in the Galway suburbs, I was keenly aware that Eavan had celebrated the ordinary wonders of a woman’s life in the suburbs of Dublin, elevating the everyday granular details of her reality to art, like her great mentor, Patrick Kavanagh, before her had done for the small farms of rural Ireland. I felt truly free to write about my struggles with breast feeding, about adjusting to motherhood, about the vicissitudes of parenting a child with special education needs and also about attuning to the quiet joys of children, the wonder of “night feeds”, the miracles amid the challenges.

In sum, Eavan Boland has bequeathed us many treasures; we are blessed to be able to enjoy her rich legacy. If you are not familiar with her poems, now is a great time to seek them out on sites such as Poetry Foundation or Poem Hunter.com for starters. Ar Dheis De go raibh a h-anam.

Although it’s a sombre week to embark on a new adventure with technology, in the wake of Eavan's passing, I will be giving my first live youtube reading for the Holding Cell tomorrow evening (Wed, 29 April) at 7pm and the poet's generous legacy and spirit will be foremost on my mind. Please join me live from my kitchen at 7pm by clicking here.https://youtu.be/YJemsDRXwyU

Thursday, April 9, 2020

A few thoughts about poetry for National Poetry Month

Happy National Poetry Month! Launched by the Academy of American Poets in April 1996, this occasion was conceived to remind the public that poetry matters and that poets have a vital role to play in our culture. It has since become the largest literary celebration in the world, with millions of readers, students, teachers, librarians, booksellers, curators, publishers, and, of course, poets, marking poetry's important place in our lives.

Through the centuries, humankind has reached for poetry in volatile times for a variety of reasons. We turn to it for solace and comfort, for inspiration and distraction, for sheer beauty of image and word music, to attenuate our loneliness and isolation, to remind us of our common humanity and the uncommon reach of our souls, to motivate us for change and revolution. Sometimes the volta of a poem is the vital lever we need to pivot around our dogging worries, to jolt us into action with a fresh resolve.

It is also true to say that people sometimes find poetry obscure, that it can challenge us as readers. There is a sense in which we can get hung up on its explainability, however. Christopher Logue wisely uttered that “poetry cannot be defined, only experienced,” something which Billy Collins articulated memorably in his poem, “Introduction to Poetry.” One of the pleasures of reading poetry is mulling over its reverberations, over that which might elude us at first. Jane Hirshfield expresses this beautifully in Hiddenness, Uncertainty, Surprise: "A poem's comprehension does not require conscious consent. We extrapolate the existence of the riddle, not just its solution, from the clues, in a process mostly beneath the surface of awareness." If I find myself grappling with a poem – (even poets do this on occasion!) - I try to encounter the poem on its own terms, rather than dismiss it as arcane. “If a poem is completely confusing,” writes Rhian Williams in The Poetry Toolkit, “start with listening for its sounds, marking its rhythms, thinking about its form. These starting points can open up a route to a more satisfying understanding.”

As we confront the unchartered territory of a global pandemic, National Poetry Month is a welcome light to help us navigate through this darkness. In our recent history, poems such as W.H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939” which found the poet “uncertain and afraid” at the outbreak of World War II, gained new resonance in the wake of 9/11. Though it invited some controversy too, the poem, which moves beyond stasis, took on a quasi-religious status, with Auden “showing an affirming flame” at its end. Similarly, Brendan Kennelly’s poem “Begin” touched, and was shared by, many New Yorkers in the days after the attacks. In terms of its power to inspire revolution, we recall that poetry played a crucial part in the Peace Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, the Gay Liberation Campaign and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. During the more recent Arab Spring, four lines of poetry from Abu Al-Qasim Al-Shabi’s poem “Will to Live,” captured the emotions of Tunisian protesters in their struggle for democracy and proved a powerful, unifying cry for freedom: ‘If one day, a people desire to live, / then fate will answer their call / And their night will then begin to fade, / and their chains break and fall.’ This quatrain was repeatedly uttered, emblazoned on t-shirts and shared orally & across social media. I have written elsewhere on this blog about how the silenced women of Afghanistan are harnessing the power of the two-line landay form as a platform of resistance.

Last year, in my role as Director of Cuirt International Festival of Literature, I was thrilled to be able to bring two powerful spoken word poets and activists to Galway audiences: Palestinian poet, Rafeef Ziadh and African-American poet, Patricia Smith. You can hear their gripping performance, which was hosted by Olivia O’Leary and recorded live at the Town Hall for RTE Radio 1’s Poetry Programme at this link. (Also note that Cúirt will be going digital this year and will be broadcast online and entirely free. Congratulations to new Director, Sasha de Buyl and all the festival team on a great initiative!).

It is also true to say that people sometimes find poetry obscure, that it can challenge us as readers. There is a sense in which we can get hung up on its explainability, however. Christopher Logue wisely uttered that “poetry cannot be defined, only experienced,” something which Billy Collins articulated memorably in his poem, “Introduction to Poetry.” One of the pleasures of reading poetry is mulling over its reverberations, over that which might elude us at first. Jane Hirshfield expresses this beautifully in Hiddenness, Uncertainty, Surprise: "A poem's comprehension does not require conscious consent. We extrapolate the existence of the riddle, not just its solution, from the clues, in a process mostly beneath the surface of awareness." If I find myself grappling with a poem – (even poets do this on occasion!) - I try to encounter the poem on its own terms, rather than dismiss it as arcane. “If a poem is completely confusing,” writes Rhian Williams in The Poetry Toolkit, “start with listening for its sounds, marking its rhythms, thinking about its form. These starting points can open up a route to a more satisfying understanding.”

As we confront the unchartered territory of a global pandemic, National Poetry Month is a welcome light to help us navigate through this darkness. In our recent history, poems such as W.H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939” which found the poet “uncertain and afraid” at the outbreak of World War II, gained new resonance in the wake of 9/11. Though it invited some controversy too, the poem, which moves beyond stasis, took on a quasi-religious status, with Auden “showing an affirming flame” at its end. Similarly, Brendan Kennelly’s poem “Begin” touched, and was shared by, many New Yorkers in the days after the attacks. In terms of its power to inspire revolution, we recall that poetry played a crucial part in the Peace Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, the Gay Liberation Campaign and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. During the more recent Arab Spring, four lines of poetry from Abu Al-Qasim Al-Shabi’s poem “Will to Live,” captured the emotions of Tunisian protesters in their struggle for democracy and proved a powerful, unifying cry for freedom: ‘If one day, a people desire to live, / then fate will answer their call / And their night will then begin to fade, / and their chains break and fall.’ This quatrain was repeatedly uttered, emblazoned on t-shirts and shared orally & across social media. I have written elsewhere on this blog about how the silenced women of Afghanistan are harnessing the power of the two-line landay form as a platform of resistance.

Last year, in my role as Director of Cuirt International Festival of Literature, I was thrilled to be able to bring two powerful spoken word poets and activists to Galway audiences: Palestinian poet, Rafeef Ziadh and African-American poet, Patricia Smith. You can hear their gripping performance, which was hosted by Olivia O’Leary and recorded live at the Town Hall for RTE Radio 1’s Poetry Programme at this link. (Also note that Cúirt will be going digital this year and will be broadcast online and entirely free. Congratulations to new Director, Sasha de Buyl and all the festival team on a great initiative!).

It is heart-warming that many people are currently sharing and exchanging poems again; poems such as "Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver with its potent lines “whoever you are, no matter how lonely, / the world offers itself to your imagination”, Wendell Berry's "The Peace of Wild Things" and John O’Donoghue’s “This is the time to be slow, / Lie low to the wall / Until the bitter weather passes.” The American poet and activist, Audre Lorde stated that “. . . poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of light within which we can predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change.” My hope is that our collective sharing of our favourite poems during this international crisis and beyond, will saturate the world with poetry and remind us of its very real power to inspire, comfort, delight and affirm. And, in so doing, illuminate the quality of light within our own lives. If you would like to receive a free daily poem in your inbox, I would encourage you to do sign up for up for a Poem-a-Day and also to subscribe to the Poetry Foundation's Poem of the Day.

As a champion of poetry and poets, through the courses that I teach (‘Creative Writing’ to undergraduates and ‘Appreciation of Poetry’ for Adult Education at NUI Galway) and through the various arts events and activities I organise from time to time, I have assembled quite a storehouse of thoughts and ideas about the form, some of which I’d like to share with you here. I hope they might bring a little bit of comfort and inspiration at this time of uncertainty.

On how poetry is born:

· “A poem begins as a lump in the throat, a sense of wrong, a homesickness, a lovesickness.” – Robert Frost

· “You can find poetry in your everyday life, your memory, in what people say on the bus, in the news, or just what’s in your heart.” – Carol Anne Duffy

· “Poetry is everywhere; it just needs editing.” – James Tate

On what poetry is – expressed in a poem:

‘Poetry is that

which arrives at the intellect

by way of the heart.’

- R.S. Thomas

On the sensations of poetry – some ‘slanted truths’:

· “If I read a book and it makes my body so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it.” – Emily Dickinson

On poetry and the mind:

· “Poetry is a great mental accelerator” – Joseph Brodsky

· “Poetry is an espresso shot of thought” – Daljit Nagra

On poetry and the heart:

· “Poetry is the universal language which the heart holds with nature and itself.” – William Hazlitt

On the uplifting nature of poetry:

· “Poetry excites the moment with hope.” – Patrick Kavanagh

On poetry and humanity:

· “A good poem is a contribution to reality. The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. A good poem helps to change the shape of the universe, helps to extend everyone's knowledge of himself and the world around him.” - Dylan Thomas

· “It [poetry] is a widening of consciousness, an extension of humanity. We sense an ideal version when we read, and with it arm ourselves, to quarrel with reality.” – David Constantine

On poetry and music:

· “Each word has a little music of its own” which “poetry arranges so it can be heard” - Kenneth Koch

“The poet is the bearer of rhythm. In the infinite depths of the human spirit, which are beyond the reach of morality, law, society and the state, move sound-waves akin to the waves embracing the universe…” – Alexander Blok

“The poet is the bearer of rhythm. In the infinite depths of the human spirit, which are beyond the reach of morality, law, society and the state, move sound-waves akin to the waves embracing the universe…” – Alexander Blok

· “Poetry is the music of being human.” – Carol Anne Duffy

“Poetry atrophies when it gets too far away from music.” - Ezra Pound

“Poetry atrophies when it gets too far away from music.” - Ezra Pound

On poetry and language:

· “Poetry is language at its most distilled and powerful.” – Rita Dove

· “Poetry is the art of using words charged with their utmost meaning.” – Dana Goia

“Poetry is a fresh look and a fresh listen.” - Robert Frost

On poetry and silence:

· “Poetry is the place where language in its silence is most beautifully articulated. Poetry is the language of silence… One way to invigorate and renew your language is to expose yourself to poetry.” – John O’Donoghue

· “The true poem rests between the words.” ― Vanna Bonta

On poetry and the 'Poetic':

· “All genuine poetry in my view is anti-poetry.” – Charles Simic

On poetry and truth:

“The ethical responsibility of the poet is emotional accuracy.” – Helen Vendler

“The poet is a liar who always speaks the truth.” - Jean Cocteau

“The ethical responsibility of the poet is emotional accuracy.” – Helen Vendler

“The poet is a liar who always speaks the truth.” - Jean Cocteau

· “A poet must never make a statement simply because it sounds poetically exciting; he must also believe it to be true.” – W. H. Auden

On poetry’s revolutionary power:

· “Poetry is the lifeblood of rebellion, revolution, and the raising of consciousness.” - Alice Walker

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)